The “outlaw couple” is far from a fresh topic in American cinema. Classic films like Gun Crazy directly inspired the New Hollywood milestone Bonnie and Clyde(1976). Terrence Malick’s debut feature, Badlands (1973), pays homage to this lineage, Arthur Penn was actually the director’s neighbor.

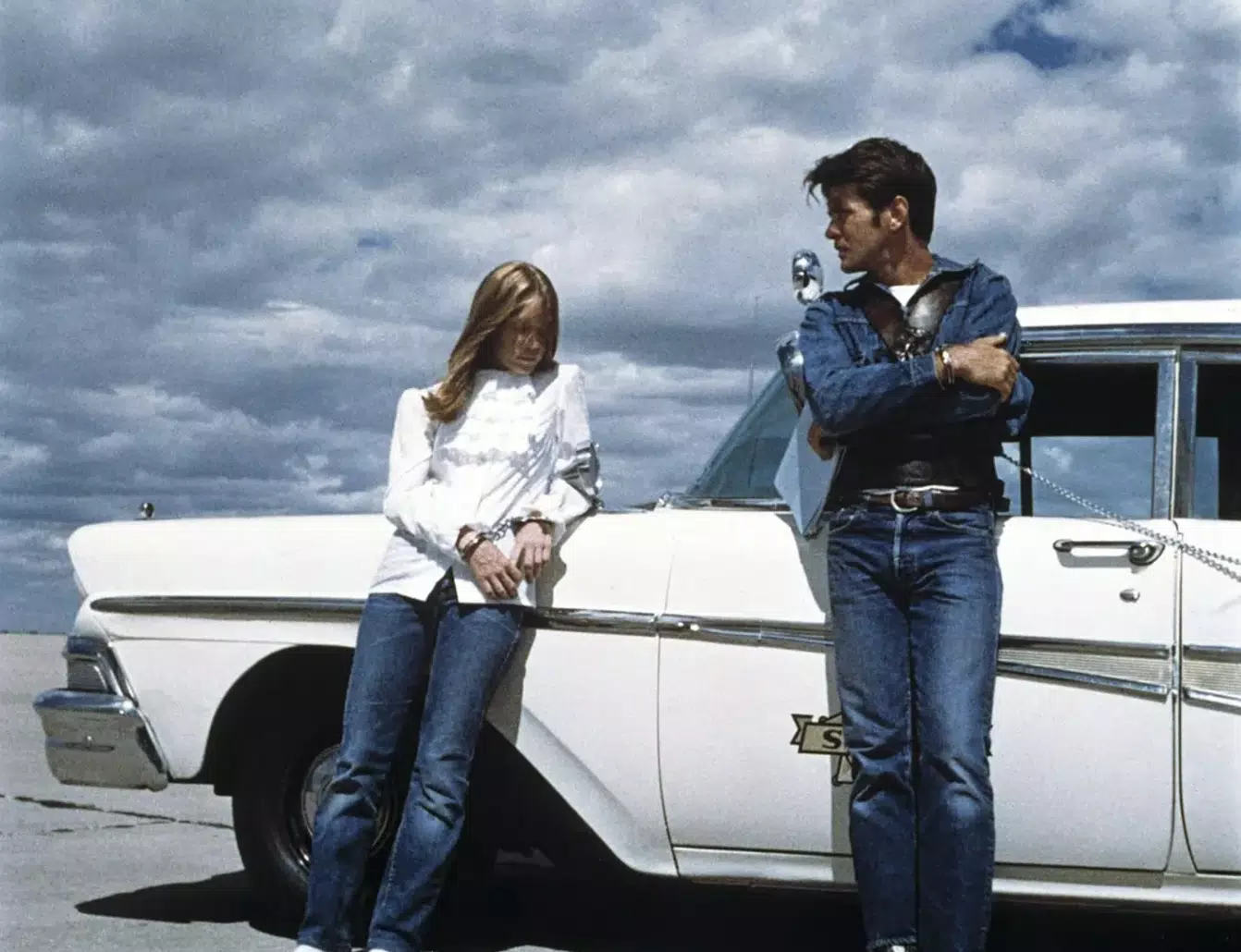

Badlands tells the story of a fugitive couple. Kit (Martin Sheen), a “garbage collector”, falls for Holly (Sissy Spacek), a girl strictly controlled by her father. After killing Holly’s father, Kit and Holly embark on a journey through the desolate plains of South Dakota. Although the narrative is steeped in violence and bloodshed, Badlands stands apart from conventional road movies like Bonnie and Clyde. Malick’s film is infused with a unique philosophical perspective and poetic imagery. It avoids graphic violence and instead juxtaposes the brutality with the serene vastness of the Midwest, creating an almost pastoral dreamscape. As the film’s production designer Jack Fisk aptly remarked, “Malick is like a philosopher.”

Much like Bonnie and Clyde, Badlands draws inspiration from a real-life story. In 1958, 19-year-old Charles Starkweather went on a killing spree with his 14-year-old girlfriend, Caril Fugate, murdering ten people in a matter of weeks. Starkweather was executed for his crimes, while Fugate received a life sentence.

In the movie, Holly’s life takes a dramatic turn when she meets Kit. The boy, with a charm reminiscent of James Dean, captivates her, despite the evident danger lurking beneath his exterior. When Holly’s father forbids their relationship, a confrontation ends tragically—Kit kills her father. This marks the beginning of their life on the run. Holly’s detached reaction to her father’s death is chilling. Emotionally removed, she seems to exist outside the gravity of events. After the murder, Kit sets fire to their home to stage a fake double suicide. Unlike the banjo-fueled frenzy in Bonnie and Clyde, the score in Badlands evokes a ritualistic reverence for violence, underscoring Kit’s unsettling obsession with pure, unadulterated evil.

Kit began his killing spree in a state of detachment, as if he had lost touch with reality. He knew he had made a grave mistake but saw no way to fix it. Unable to reconcile with his actions, he turned to escape—an instinctive response when faced with irreparable errors. This is human nature: when there’s no way to make amends, people seek a concrete, tangible action to assert control, to convince themselves that things haven’t spiraled entirely out of their grasp. From that moment on, we can no longer judge them by normal moral standards, as they have broken free from the constraints of ethics and law, becoming something akin to human animals.

But why do they continue to kill? Primarily, it’s Kit who drives the violence. It looks like, Holly, still too young and inexperienced, lacks the capacity to make significant judgments or to stop him. Influenced by societal and cultural narratives, Kit may perceive himself as a kind of hero. Yet within the details of their actions lies the cruelty of children: their game-like approach to everything, including their disregard for others’ lives and suffering.

And it is precisely these scenes that pose the essential question: what should we do? Are we inherently cruel? Or are we simply numb? The film doesn’t give answers but instead challenges us to confront these unsettling truths.

Holly, however, presents a more complex form of evil. She is seemingly innocent yet entirely devoid of moral discernment. Watching Kit kill repeatedly during their escape, she remains passive, unable, maybe unwilling to acknowledge the horror. Holly’s emotional barrenness is rooted in her upbringing. Orphaned at a young age, she was raised by an emotionally distant father who failed to teach her love or empathy. Acting on childlike instincts, Holly stumbles into an adult world where every act comes with consequences. Her cold indifference becomes a form of unspoken revenge against society. She is not merely an agent of male corruption; rather, she serves as the trigger for Kit’s violence. But is that really the case?

Toward the film’s conclusion, Holly begins to awaken to her own humanity. During their final pursuit, she chooses not to flee and allows herself to be captured alongside Kit. This act of surrender seems less a moral reckoning and more a reflection of her fading love for Kit. With her emotional anchor gone, Holly can no longer find any allure in their fugitive existence.

Kit and Holly’s characterizations are riddled with contradictions. They are like Adam and Eve—innocent yet primal—leading viewers to momentarily overlook their crimes. Kit is a charismatic but immature young man, rebelling against societal norms more out of defiance than malice. Holly, suppressed by patriarchal control, is drawn to Kit’s rebellious spirit. Through their eyes, Badlands romanticizes crime and portrays their violent odyssey as a poetic escape.

Malick’s approach to storytelling avoids direct critique or moral judgment, opting instead to explore crime through the lens of “unawareness.” This perspective softens the harshness of violence, yet it forces viewers to grapple with an unsettling question: how can such a gruesome tale feel so beautiful?

Malick frames the narrative as a tragic romance, painting the couple’s journey with idyllic tones reminiscent. Kit’s vanity—fixing his hair during a chase, smiling shyly at a James Dean comparison—even in the face of death, highlights their youthful ignorance. Holly’s detached voiceover recounts their crimes with a striking nonchalance, emphasizing the gap between their actions and their understanding of them.

This artistic choice challenges traditional crime narratives and examines how adolescent rebellion and isolation can escalate into societal defiance. Kit and Holly’s violent acts are not random—they are attempts to escape oppressive circumstances and seek freedom. Yet, as the film suggests, love as a form of rebellion is fleeting and fraught with disillusionment.

Malick delves into the mythic nature of violence, portraying Kit’s gun as a wand of power that ultimately cannot conquer loneliness or despair. Their journey is less about evading capture and more about confronting the void within themselves. While they hope to find paradise in the wilderness, they instead encounter an overwhelming sense of emptiness.

Badlands showcases Malick’s distinctive cinematic voice. Wide-angle shots of the barren landscapes, combined with Holly’s childlike narration and whimsical music, create an illusion of innocence. Yet beneath this “storybook” tone lies a current of tension and melancholy, forcing viewers to reconcile the beauty of the imagery with the horror of the actions it depicts. Malick’s use of golden light and deep blue hues during dawn and dusk scenes evokes an Edenic quality, further heightening the film’s blend of the pastoral and the sinister.

Malick intentionally downplays 1950s nostalgia to prevent period details from overwhelming the narrative. He once stated that he wanted the film to feel like a timeless fairy tale, free from the constraints of specific eras. This approach elevates Badlands beyond a mere crime story, transforming it into a profound exploration of human nature and societal constructs.

Though initially met with lukewarm reviews, Badlands has since gained recognition as one of the most influential American films. Its enduring appeal lies not only in its gripping narrative but also in its ability to provoke deep reflection on morality, identity, and the human condition. Malick’s poetic rendering of violence and love ensures Badlands remains a timeless meditation on the complexities of existence.

Share your thoughts!

Be the first to start the conversation.